All About Fusions

This is Part 15 of a serial blog post. In Part 14, I share detailed information on three popular exercise methods that specifically target scoliosis: Scolio-Pilates, The Schroth Method, and ScoliSMART. In Part 13, I talk about options for managing scoliosis and offer a glimpse into the depth of study, time and training it took to get certified to teach Yoga for Scoliosis. Missed the earlier posts? Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8, Part 9, Part 10, Part 11 and Part 12.

Did you know that June is Scoliosis Awareness Month? And that June 30th is International Scoliosis Awareness Day… every year?

To mark this occasion, this blog is all about something I know very well: Fusions!

I realize that I often talk about people having scoliosis as being ‘one thing’, when in reality, a non-fused scoliosis and a fused scoliosis can be two very different things. There are more people with scoliosis without fusions, so people with fusions are often the minority.

To give the fused folks some extra love this month, I am writing about fusions in general, and my own surgical journey, in addition to the overall impact of having a fused spine. I have also included links to information on different surgical methods and how they are evolving.

About Scoliosis Fusions in General:

Statistics show that 2-3% of the population is affected by scoliosis. About 10% of all adolescents have some degree of scoliosis, but less than 1% of them need treatment. Females are 8 times more likely to need treatment than males. Treatment options include physiotherapy or other rehabilitation techniques, bracing, and, for severe cases, surgery.

Most surgeons agree that children who have very severe curves (45-50°+ as measured by the Cobb Angle) will need surgery to straighten the curve and prevent it from getting worse. For the most common type of scoliosis, Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis, surgery is recommended while the teenager is still growing.

The surgery used to treat scoliosis is spinal straightening and, in most cases, fusion. The basic idea behind this surgery is to realign and fuse together the curved vertebrae so that they heal into a single solid bone which will not curve anymore.

Although the tools and technology today allow surgeons to improve curves significantly, this does not mean that after surgery the scoliosis is ‘cured’. Nor does it mean that all the problems caused by scoliosis will disappear. In fact, it is very common for fusion surgery, especially the older versions, to cause other problems—sometimes many years after the initial surgery.

It is not easy to live with a very curved and twisted spine; the disabling effects of pain and discomfort from asymmetry affect the whole body. The idea of ‘fixing it’ with surgery feels very promising—and often surgery can be very helpful, making the spine appear much straighter, and relieving discomfort from compression. During the first several years following the operation, after the initial healing is done, patients, especially the adolescent ones, are often pain free. Many succeed in staying very active, in sports, dance, and some even in running marathons.

Nevertheless there always seem to be tradeoffs. Here are a few:

Like any surgery, complications may include infection, blood loss, and nerve damage.

Although the spine LOOKS straighter, there are still curves and twists that cause compression and pressure. Sometimes, even with the surgery, the curves can get worse.

When fused, the usually flexible and mobile spine becomes very stiff, which means the rest of the body’s mobility is affected as well. This can lead to adjacent segment disease when the vertebrae above and below the surgery are damaged due to the extra load caused by the fusion. As a result, long-term complications include degeneration at these adjacent spine segments.

In some cases, the spine is straightened too much, causing something called ‘flatback syndrome’. This happens when the surgery over-corrects the natural lordotic curve at the waist and/or neck, or the natural kyphotic curve in the upper back.

The instrumentation that is implanted in the body to help straighten the spine can change over time, becoming detached or actually breaking. Additionally, surgical steel can leave metallic traces in the body which can sometimes cause poisoning or allergies.

Martha’s Fusion Story:

When I was recommended treatment in 1973 at the age of 13, I was told that I could either wear a brace for three years, and probably still need the fusion, or I could have the fusion right away and get it over with in a year.

Hmmm. Not much of a choice for a 13 year old girl who loved to dance.

I was sent to a very inept physiotherapist for a few weeks, but my mother deemed her so cruel and unhelpful that we stopped going. Aside from the awkward exercises she showed me, I remember her scowling at me, and telling me it was my fault I had scoliosis because I was a lazy teenager with bad posture. She made me feel scared and humiliated.

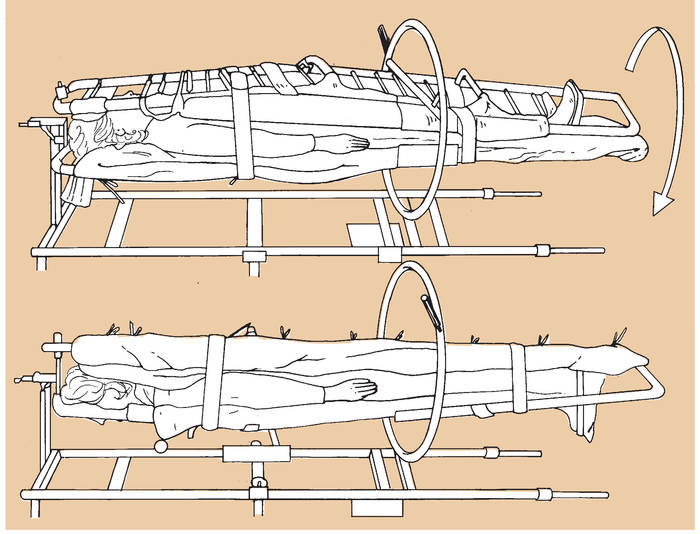

Example of Traction

Credit: Suzanne Ayella Holton

Other than that, no other exercise or other non-surgical suggestions were made.

Within a few months, it was decided that I would have Harrington Rod fusion surgery, and the process started. In retrospect, I am not sure how this decision was made, but I willingly went along as it somehow seemed easier than wearing a brace for three years.

The beginning of my journey involved being put in traction in the hospital for three weeks because the Doctors wanted to loosen my tight and twisty curve first. They felt that due to strong muscles from ballet, my vertebrae would resist being changed unless they were opened and stretched before the surgery. I have since learned that this was quite common in the early days of surgery.

With 50 pounds of weight on my head and 50 pounds on my hips, I lay there, staring at the ceiling, for 23 hours a day, getting stretched in opposite directions. I remember feeling very restless, mostly due to a terrible pain in my jaw. The weight on my head was held on by a strap under my chin, so every time I opened my mouth, I was basically lifting 50 pounds with my jaw. I was not a happy camper.

The traction was not as successful as they had hoped, so they decided to move on to Plan B. This meant trying to loosen the vertebrae by stretching me ’against my curve’ in a cast. The process of getting this cast was as bad or worse than the traction. Wearing only a thin gauze tube around my torso, I was laid on a cold metal ‘casting’ table while three Doctors (all male), pulled my arms, legs and torso in three different directions to counteract my curve, as a fourth Doctors slopped cold, wet plaster gauze all over my torso. I felt very exposed and vulnerable, not to mention completely horrified at being trapped in a hard, twisted, uncomfortable cast from armpit to pelvis. I distinctly remember that as they worked, they ignored me and talked about golf!

Example of Casting Traction

Back at home, I could only find one or two things that fit me. It was a hot summer, so my favourite thing was to simply wear my mother’s large, white, stretchy tennis shorts, as they pulled up over my cast. My brother teased me that I looked like a walking egg, which was true. At least I didn’t have to go to school; I could just hide at home. The cast was hot and sticky and incredibly awkward. I remember getting stung by a bee on my leg because I couldn’t bend over to swat it away!

Example of Body Cast

Following several weeks in that cast, I was finally scheduled for surgery.

The night before, I remember being in the hospital and feeling very alone and anxious. A kind nurse came in, and she shaved my back and legs, and commented that I had very hairy knees. And when morning came, I was wheeled down the halls of the hospitals, feeling drowsy from medication and watching the lights flash above me as we entered the surgery room. I remember the Doctor putting something over my mouth and telling me to count backwards from 10.

“Ten, nine, eight…”

And then, suddenly, the surgery was over, and I woke up and I was in SO much pain. I was tied into a bed, and though my arms were free, I could hardly lift them. I had a bad reaction to the anaesthesia, and immediately started puking, my body racking with pain as I convulsed. They had those old kidney-shaped dishes to get sick in, but since I couldn’t move, I had to call the nurse every time I started feeling nauseous. One time a nurse leaned in to give me the puke dish and my vomit ricocheted off the dish, hit the chest of her uniform, bounced to her forehead and then splashed up to the ceiling!

I got to stare at that green smear on the ceiling for the entire duration of my stay in hospital.

To ensure the fusion connected properly, I was put in a stryker frame. A stryker frame is a special hospital bed where the patient is strapped into a frame to completely immobilize the spine. Every four hours the nurses would come to flip me over to my other side. Front, then back, then front, then back. This was accomplished by putting another ‘mattress’ on top of me so that I was like a sandwich. Then they would flip the whole ‘sandwich’ over to keep me from getting pressure sores. I lay there for three weeks.

By all accounts, the fusion surgery was a success. My curve had reduced from 54° to 27° and I stood 3 inches taller. After my time on the stryker frame, I was sent back to the casting table where I was wrapped in another plaster body cast, but this time without being pulled by the legs and arms. I wonder if they gave me sedation that time - I remember feeling incredibly fragile.

Afterwards, I was sent home in an ambulance where I was required to lay flat in bed in the body cast for several months. I could lie on my back, my front, or my side with the right kind of pillow props. Occasionally, I was helped down on to the floor where I still had to lay flat, but could literally roll around!

In some ways, I enjoyed all the attention. The local school board assigned me a lovely tutor who came to my home so I could keep up with my studies. My folks jokingly gave me a silver bell to ring whenever I needed something… and I used it every day! I will forever be grateful for my whole family answering to that bell… especially when it came time for the bedpan. Yikes! To keep me entertained, my Dad splurged and bought the family’s first colour TV with a remote, which at the time was the size of a small brick. The TV was put in my room where I developed the habit of watching Johnny Carson every night after the family went to bed.

Finally, after about four months of bed stay, the ambulance drove me back to the hospital to have the cast removed. After checking that my incision had healed correctly, they immediately put me in ANOTHER plaster cast, but this time it was a walking cast. After surviving a third go at the cold metal table, I thought the worst was over... but no such luck!

Without any notice, the nurses arrived in my room and told me to stand up. Of course I wanted to get up, so I enthusiastically tried, but quickly realized that I was so weak that I couldn’t stand, and I was so dizzy that I felt like I was going to faint. I had barely got into an upright position when I fell back onto the bed.

What they were thinking? In retrospect, this was an irresponsible request. I had not stood up for about five months, so why didn’t they ease me into a sitting position before a standing position?

What if I had fallen to the floor? And hit my head going down?

That was one of the most scary and stressful moments for me because I had all the energy I needed, but no awareness or wisdom. My body felt completely different (duh) and I felt completely disconnected from it.

After another two months, the last body cast was removed and I was finally free!

Thinking back, that was another kind of crazy moment. The Doctor sawed off the cast, which in itself was terrifying. He had me lie on one side, then he casually stuck the whirring saw straight onto my other side, and it made this horrible high pitched sound as it broke the plaster and revealed my skin. AFTER, he showed me that the saw was not sharp to the skin. It would have been nice to know ahead of time!

After that initial trauma, he peeled off the cast, which left me topless and exposed for the first time in about six months. Without giving me a chance to put anything on, he asked me to stand up and walk in a straight line back and forth in front of him a few times. By then I was 14 years old, and felt incredibly self-conscious. It felt like all the Doctors, throughout my treatment since age 11, were completely and totally oblivious to that. It was common practice for several of them to come into the examination room where I was required to stand topless in just my underwear with my arms to my side, and turn slowly, as they observed my back. I must have done this dozens of times.

And then, almost as if it never happened, my mother and I said goodbye to the Doctor and walked out the hospital doors, without ever looking back. Nobody gave me any instructions on how to manage my new body. It was just, “Goodbye, and have a good life!”

At first, I felt very fragile, and it took me several months to get my strength and energy back. But in general, my teenage resilience got me moving again quite quickly. I don’t remember having any major problems, even when I started dancing again. I wasn’t really supposed to, but I discovered contemporary dance which was more forgiving than ballet. I had some aches and pains, and I felt very stiff, but over time I learned to enjoy moving in a new way. At least I could do what I loved - and over time, dance became very healing for me.

Unfortunately, about nineteen years after surgery, l started to have terrible spasms and discomfort. With the help of some bodywork professionals, I came to the conclusion that I needed to do something to help my back feel better. Fast forward a couple more years, and I chose to have my rods removed, and a whole new healing journey began as I learned to reconnect with my spine. To read about that story, read the first 14 episodes of my blog.

The Impact of Spinal Fusion:

The more I work to find ease and mobility around my own fusion, the more I question a lot of things around my fusion and how it affects me.

Here are some questions I will be addressing at the Fusion Retreat I’ll be leading in September 2018 in Black Creek, British Columbia:

1. How does having a fusion impact a life?

2. What is the best way for people with fusions to feel safe and confident in their bodies while living day-to-day, let alone while doing exercise?

3. How can people with fusions get health benefits and enjoyment from a very methodical technique like Yoga, even when they can’t do all the poses?

4. What happens to the biomechanics of the body when the naturally scoliotic, but flexible curve gets surgically changed to a different, less natural, and now non-flexible curve? What is ‘ideal alignment’ for a fused scoliotic spine?

5. How does fusion affect all the body’s systems? ie: chakras, breath, alignment, gait, balance, proprioception, nervous system, myofascial system, etc?

6. What is the best interdisciplinary mix of exercises that will help guide people with fused spines to find freedom and softness in their limitations?

For more information about our retreats, visit our Workshop page.

Types of Fusion Surgery:

I had my Harrington Rod surgery in 1974. At the time, it was a fairly new surgery and the Doctors were very cautious, which meant I was required to lay in bed for the better part of a year. Although the surgery was deemed a success, the actual bed stay caused many additional health problems, including muscle atrophy, scar tissue build up, digestive issues, and core weakness.

Nowadays, there are many different versions of the surgery, and regardless of which one people opt for, most patients get up and start walking almost immediately after the procedure. This way, they are much more likely to recover quickly and without developing chronic issues. They adjust to the new sensation of straightness in their bodies faster, which helps to build physical and emotional confidence. Also, the short bed stay coupled with the use of removable braces rather than the heavy plaster casts are much easier on the body - and the ego!

Another positive evolution is the general understanding that scoliosis surgery can have psychological effects, causing feelings of self-consciousness, anxiety, fear, shame, depression, trauma, isolation, and more. Considering that the majority of patients are teenagers, it is great to hear that many medical professionals working with scoliosis are starting to address these issues along with the physical ones.

The actual procedure and the type of instrumentation are constantly evolving. In general, I understand that surgeons are finding ways to correct the curves without always doing bone graft fusions. Some of the ‘rods’ are actually flexible now, and others can grow as the spine grows.

To read about the many kind of scoliosis surgical techniques that are used globally, including Harrington Rod, Cotrel-dubousset Method, Intervertebral Body Stapling, Wedging Osteotomies of vertebral bodies, and more, please visit our Fusions page.

For my next blog, I will address the fact that scoliosis is a ‘confounding condition’. Based on my experience as someone with a fused spine, and my observations of others, I will share some thoughts around why I think scoliosis is so darn hard to handle…

Got comments? Please feel free to write us anytime.